Teaching Philosophy Statement

Teaching in the age of social media and artificial intelligence

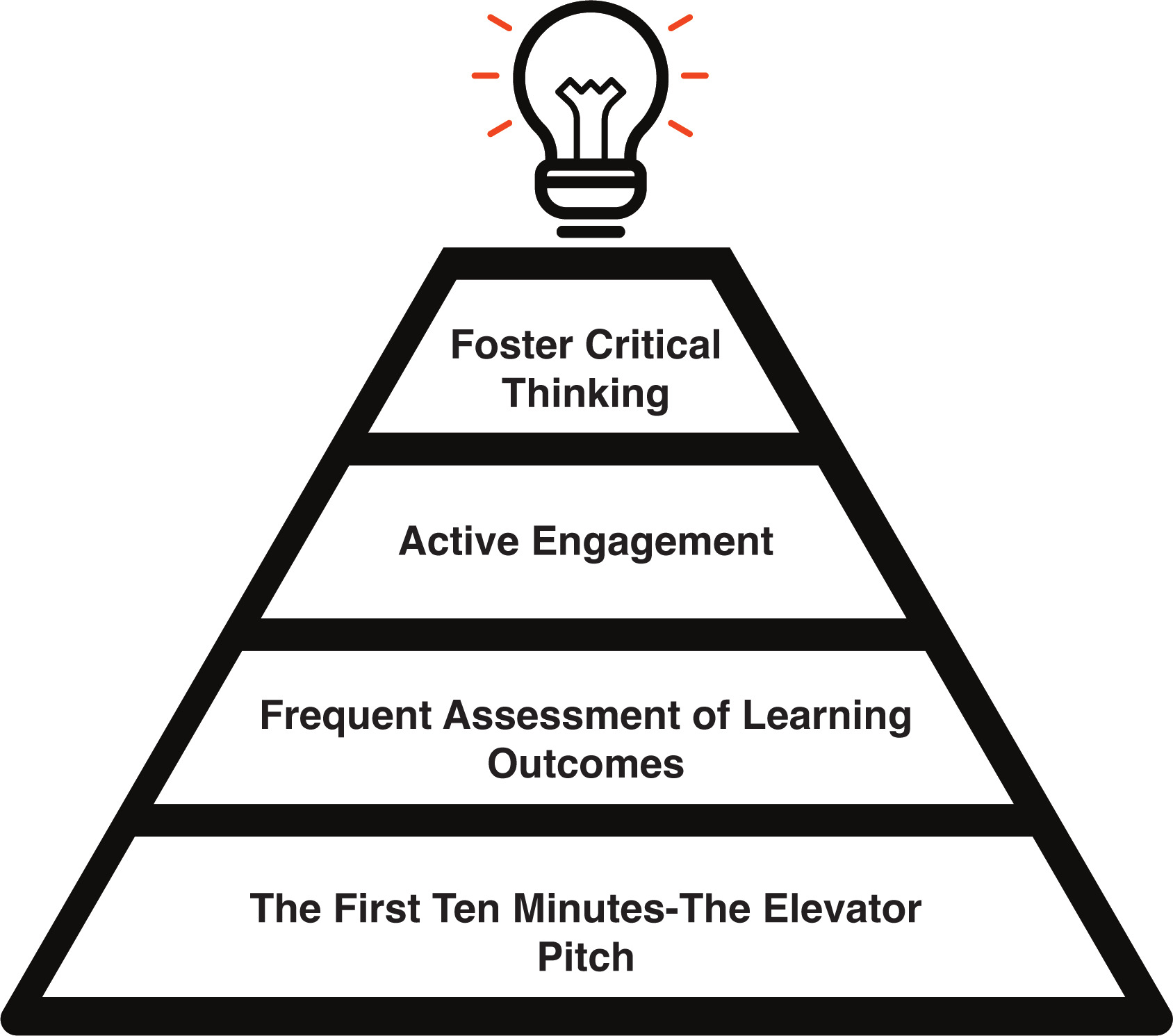

This pyramid diagram illustrates my teaching philosophy, in which I take a tiered approach to ensure students not only succeed in the classroom, but also thrive in a society rife with misinformation.

The First Ten Minutes: According to social psychology research conducted at Northwestern and Princeton, people tend to form a first impression of others based on their warmth and competence [1]. Across different cultures, high warmth and high competence tend to elicit admiration and manifest as active facilitation [1]. Therefore, I do the following things on the first day of class: get to know my students, make sure they have everything they need for their first day, go over the syllabus with them, and pay special attention not to make any mistakes. The similar philosophy also applies throughout the semester, where I tailor my opening speech in every session to grasp students’ attention and orient them to today’s tasks. Ultimately, I believe warmth and competence is key to becoming an approachable instructor.

Frequent Assessment: Are my students ready to learn? According to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: higher level needs (creativity, respect of others, problem solving, learning of facts) cannot be fulfilled unless all lower tier needs (food, sleep, physical safety, sense of belonging etc.) are met [2]. Try to learn multivariable calculus while you are in a hurry to go to the bathroom—I bet you can’t. In my 8 am class, many students are either sleep deprived and/or did not have breakfast, which makes it more imperative to capture students’ attention in the very beginning. Therefore, I create the unexpected: for instance, not many would expect to learn about the chemistry behind grape flavored Kool-Aid when they come into class at 8 am. Then, I will reveal the artificial grape flavorings are made via the chemistry we are learning that day, and an abstract reaction just becomes something they can relate to, and even have tasted before.

Active Engagement: To many students, chemistry is merely a box to checkoff on their dream medical/pharm/dental school applications. Exciting science with countless demos that would impress a crowd at a Science Fair loses touch with many young scientist-in-training. I spur my students’ interests by introducing exciting cutting-edge chemistry. For example, I designed a module where students detect and characterize trace amount chemicals from daily objects within seconds, such as residual cocaine on dollar bills and the pungent compounds in freshly cut onions. To engage students’ intellect in different ways, I want to develop a chemistry class that envelopes classical chemistry knowledge, modern statistical/programming methods, and science literacy. During my undergraduate, I learned statistical programming languages and how to make scientific figures, which are critical to my chemistry research but rarely taught in undergraduate chemistry curriculum in my school, from an undergraduate oceanography class I took for fun!

Foster Critical Thinking: Carl Sagan proposed that any functional democratic society needs citizens capable of thinking critically [3]—the event in January 2021 showed how easily people can be radicalized by misinformation propagated by shadowy figures on the Internet. I believe instructors have a social responsibility to foster critical thinking skills among students. For instance, I always encourage students to think outside of the box about the supposedly “correct” experimental procedures. With some guidance, they can always figure out more efficient alternatives. Reciprocally, students become more confident as they realize that they are knowledgeable enough to improve on an existing knowledge, and they often will seek out more opportunities to do so. My teaching philosophy hierarchy culminates with Critical Thinking because most of my students won’t remember how to synthesize a compound years after they took the class, but I hope they will have developed the necessary science literacy and critical thinking skills to make informed decisions that might affect themselves or the others.